One intriguing aspect of following and appreciating the design of diverse items such as cars, watches, and even something as mundane as spectacle frames, is that you can dismiss, or disregard, things for years on end and then suddenly undergo a complete U-turn.

As a fan of the classic 1950s and 1960s Omega Constellation Manhattan, I had always dismissed Omega’s 1982 reworking of its flagship model, known as the Constellation Manhattan, as something of an aberration from the “true” Constellation concept. Somehow for me it lacked the brand’s recognized “DNA.”

I could see that it lent itself successfully to mother-of-pearl dials and diamanté finishes, so regarded it as more of a ladies’ watch, but felt that it was otherwise something of an outlier in Omega’s range. Its initial production era coincided with the quartz period, which was perhaps another reason for overlooking it.

On top of all that, I have never seen anyone wearing one (apart from my daughter who expropriated the one I bought recently the moment she set eyes on it).

I understand that it has overall been more successful in Asia than in Europe. Nevertheless, the Omega Constellation Manhattan has been in constant production with both quartz and mechanical movements since 1982 in a series of versions that have generally remained true to the original design.

My “road to Damascus” moment occurred recently when I saw a 36 mm black-dial co-axial chronometer on display at an Omega dealer in Bordeaux.

With its dauphine hands it reminded me of my ’64 Constellation, and although I had no intention of buying it I brazenly marched in to try it on.

This is something I am not in the habit of doing: I am in this respect like our friend Agnes, a Bordeaux-based fellow Scot who struggles terribly with the concept of food and wine producers’ fairs in France because she feels that if she agrees to taste even the tiniest sample of cheese or foie gras, she has to buy a large slab of it. I was smitten.

The design of the Omega Constellation Manhattan is sometimes mistakenly attributed to Gérald Genta; an understandable error as Genta had been involved in the design of various components of the Omega Constellation over the preceding 30 years, notably the “C-shaped” case, which was the “old” Constellation’s final incarnation.

And because the Manhattan’s integrated bracelet, a complete break from the earlier Constellation design, is of course a signature feature of certain other iconic Genta designs.

In fact, the Omega Constellation Manhattan was designed by a young design student from La Chaux-de-Fonds, Carol Didisheim, who joined Omega straight after completing her studies in jewelry design at the Geneva School of Decorative Arts. Omega must have been pleased with its new hire when she came up with such an innovative design at the tender age of 26.

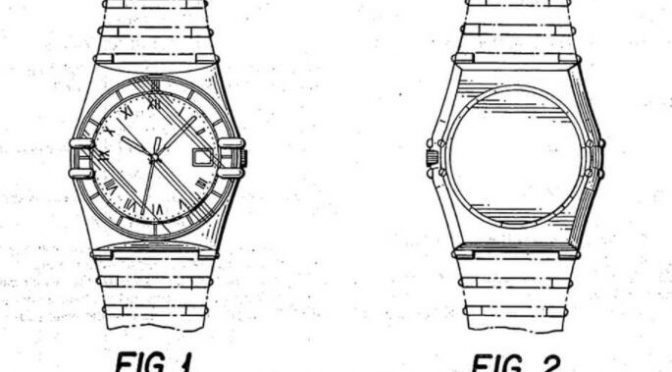

Blogger and Omega Constellation collector Desmond Guilfoyle managed to track down Carol Didisheim a few years ago, interviewing her about her involvement in the design. He learned that she had been inspired by her colleague Pierre-André Aellen’s observation of clasps holding a frameless bathroom mirror to the wall; so rather than using a bezel, the flat crystal of the new Constellation was held in place by four clasps at 3 and 9 o’clock.

This opened up possibilities for printing the hour markers on the underside of the crystal, a slimmer case profile, and improved water resistance.

What is remarkable about Didisheim’s design, which she personally patented in 1985, is that it comprises a set of design features that Omega has allowed to evolve over the years while keeping them true to the original:

Round dial

Roman numerals, initially on the dial but moving to the bezel in 1995, where they have stayed ever since

Four “griffes” (claws) at 3 and 9 o’clock inspired by hooks on a bathroom mirror; originally these ensured water resistance by holding the crystal and gasket in place

Tapered integral bracelet with distinctive link design

Distinctive scalloped case shape, sharp and yet all curves

Over the years, within this design framework Omega has issued the Omega Constellation Manhattan variously with baton hands, dauphine hands, day and date subdials, as a perpetual calendar and chronograph, and yet always in keeping with the spirit of the piece. After leaving Omega, Didisheim focused on jewelry design, but later produced another distinctive watch design for Swiss manufacturer Delance. Omega introduced integral bracelets on its Constellations as early as 1969, but these were basically a variation on Rolex’s Jubilee/President style with a narrow end link; the Manhattan’s design with its hinge bars in steel and/or gold between each link was novel and every bit as distinctive as the Ebel Wave or Audemars Piguet Royal Oak bracelets.

Originally issued in 1982 as a quartz watch with an ultra-slim ETA-based 1422 movement, there have been automatic Manhattans since 1984, originally packing Omega’s Caliber 1111 based on the trusty ETA 2892-2. But Omega has now thrown the full weight of its co-axial and Master Chronometer automatic movements behind the Manhattan, in both ladies and men’s ranges, and the results are stunning.

Here is a creation that is every bit as striking and distinctive as the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak or Patek Philippe Nautilus, but owes nothing to those designs unlike the crowd of wannabes that mimic some or all aspects of those models. Where the Royal Oak can be perceived as angular and awkward, the Manhattan is highly seductive.

Now available in 29 mm, 36 mm and 39 mm sizes, the Master Chronometer models combine George Daniels’ co-axial escapement, which allows for longer periods between services due to reduced wear, with a silicon balance wheel for improved resistance to magnetism, and both COSC and METAS (8-step) testing.

Interest in the original glass-fronted Constellations from the early 1980s is on the up (these watches are nearly 40 years old now, and who doesn’t love the 80s?).

Later models from 1990 through 2010, both quartz and automatic, represent incredible value and can be had for as little as €400. I am still kicking myself for umming and ahhing about a stunning 2010, 36 mm, blue-dial, all-steel co-axial chronometer that went for less than €700 at auction last week.

In terms of new watches, I now believe the Constellation in its latest configuration may have its best years ahead of it as a men’s all-steel sports watch; mechanically it is now a heavy hitter punching above its weight ticking all the boxes in terms of design, but does not in any way mimic the two Genta-designed behemoths that dominate this market: the Patek Philippe Nautilus and the Audemars Piguet Royal Oak.

According to the Omega website and app, prices start at €5,100 for the 38 mm co-axial chronometer and €5,500 for a diamond-free ladies 29 mm Master Chronometer, going up to more than €25,000 for the “iced” models. But the slightly older black-dial 38 mm co-axial chronometer version I tried on recently can still be had for €3,700 from authorized dealers.

However, for anyone looking for a Royal Oak or Nautilus alternative, filtering the men’s watches down to an all-steel, blue-dial version on the Omega website generates an “Oops, something went wrong” error message.

Could this be a deliberate strategy by Omega to ensure that this watch carves its own niche?